New research aims to unearth ‘hidden’ HIV

Researchers have identified a way to unearth 'hidden' HIV cells, which will provide vital information towards finding a cure for the disease.

The research team, led by The Alfred Department of Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Unit head Dr James McMahon, will use a new method of identifying latent HIV cells that have traditionally been difficult to target.

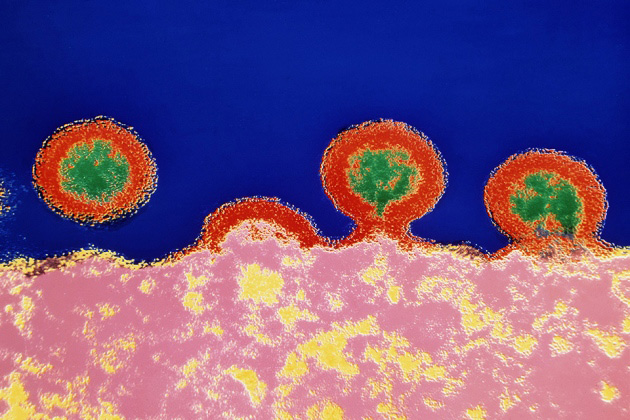

Once a person with HIV starts treatment, the amount of virus in their blood quickly drops. With regular treatment, the HIV becomes ‘undetectable’. However, this doesn't mean that HIV is eliminated from the body. The virus retreats to hiding places, mostly in the tissues, where it lurks and waits. This is HIV latency, which is the major barrier to an HIV cure.

Latent HIV hides in places like lymph nodes and the lining of the gut. Currently, the HIV remaining in these places can only be detected through invasive procedures such as biopsies, which can be risky. They only allow a small part of tissue to be studied and may not sample the exact spot where the greatest amount of HIV is hiding. There’s also a limit to how many and how often biopsies can be done.

"We need better ways to determine the amount of residual or latent HIV in people on treatment and where this virus is hiding if we are to develop ways to tackle this remaining virus," Dr McMahon said.

"This study aims to develop a non-invasive way to see HIV in the body. It will enable researchers to see where and how much HIV remains in people with HIV infection who are on treatment."

The researchers will combine an anti-HIV antibody (called 3BNC117) with a radioisotope or label (called copper-64). Researchers will then inject a small dose of this labelled antibody into study participants. The antibody will bind to HIV and cells infected with HIV and give out a signal that can be detected on a scanner.

The scanner combines Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET). The scan will detect exactly where in the body the HIV cells are.

Dr McMahon said the team can then 'wake up' the dormant HIV cells, making the virus more visible to treat.

“We have been able to link radioactive copper to an anti-HIV antibody that binds to the great majority of HIV cells in an individual. We then do a scan to detect the amount and location of the radioactive copper, and therefore identify sites of HIV,” Dr McMahon said.

“We can then infuse the copper-antibody combination with a drug to reverse HIV from its dormant state, making it more visible, and telling us where in the body this latency-reversing drug is having an effect.”

Dr McMahon has recently received a grant from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium to extend this project.